Interview with Karel Martens

Interview with Karel Martens at his Amsterdam studio, April 6, 2010

Text Harmen Liemburg for Étapes design and visual culture, international edition #21, September 2010

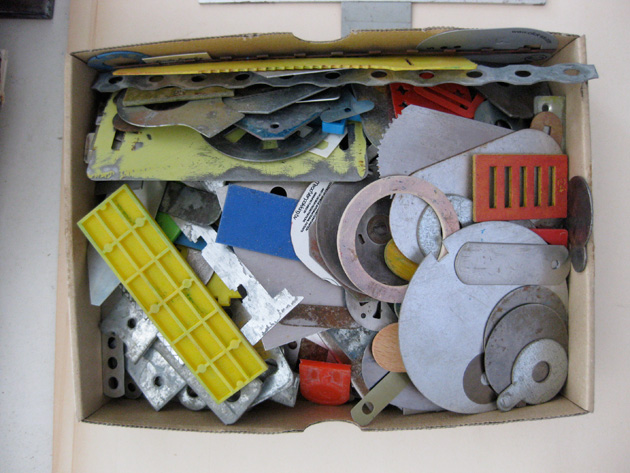

At the age of 71, with a career that spans almost half a century, Karel Martens is active as ever. When I meet him in his industrious Amsterdam studio at the water last week, he’s busy reviewing changes to the extended third edition of Printed Matter\Drukwerk that is soon going to press and should be available this fall. There’s a couple of computers on a small desk, and rows of shelfs are filled to bursting with books and archival boxes. A prominent space is taken by a small oldfahioned printing press and an inkstained workbench filled with tools and various small metal objects. One of his legendary Chinese indigo blue working jackets is hanging over a chair…

HL

Throughout your work you’ve experimented plenty by manipulating the printing industry’s standard CMYK protocols. You’ve recreated images through type, developed your own strategies to create patterns, but you hardly ever used symbols as such. Until recently, where the halftone dots are replaced by layers of various vector elements. What caused it?

KM

A birth announcement for my grandson (2002, Zeno) seems to be a moment in my live that I start to work with icons. The desire had been there for some time. Every designer or student seems to rediscover the crude halftone at some point, but I’ve always thought how nice it would be to create different shapes instead of dots. My father’s typewriter always fascinated me. I’d hit a button and the letter ‘a’ appears. But that ‘a’ might as well be a bird or another picture, something I’ve developed with Roelof Mulder for Emigré magazine (1992, Starface font made out of moviestar’s faces). Ten years later I had the opportunity to figure out how to reconstruct Zeno’s portrait in a different way.

HL

Many people would like to know the secret…

KM

Well, it’s relatively simple, and I’m sure others have discovered how to do it as well, but I’m not going to tell you anyway! This assignment (2001, façade Cultureel Centrum) is about the perception of separate colours at close range and the mixing colours that one percieves at a distance. The fact that you can create a third colour out of two, is something that never ceases to exite me. It’s nothing less than a miracle! The problem here was to translate this idea (that was developed in Photoshop) into prints on large glass panels. Screenprinting proved to be too expensive, but after a while I found a company that could print on transparent material. As they needed vector outlines, this caused a neccesity to come up with a workable system to make that technical translation, which we finally did.

HL

What did this discovery mean to you at the time?

KM

Haha, well, feelings of thriumph of course! There’s also somewhat of a danger, because now I can use it in for all kinds of applications like the pattern design for Maharam (2008, fabric design developed with KM’s daughter Klaartje Martens) and other things. Although these designs are linked with earlier letterpress monoprints that were published in Counterprint (2004, Hyphen Press) as well. Also, the façades in Haarlem (2002, Philharmonic concert hall) and the tile project in IJburg (2010, in process), were created by using similar tools.

HL

One of the reasons why PM is such a popular book must be the fact that you’re so generous sharing your working process and project backgrounds. In a way you’re teaching through the publication as well.

KM

Well, I don’t know… I’m not sure if I’m such a brilliant designer really, but I do like teaching very much.

HL

What I mean is that although the book is a of course a beautiful object with lots of appealing pictures, it requires a serious time investment from the reader to really get into the dense layers of information. In a way, the reader is invited to study.

KM

You should know that this is merely to the merit of editor and designer Jaap van Triest, who’s books are always full of information. Of course I contributed my share of time and energy, but the concept is Jaap’s.

HL

Recently in Dutch design education, there’s been a strong focus on intellectual aspects. I’m not only talking about theoretically biased schools like the Jan van Eyck academie, but also at the Rietveld academie and the Werkplaats Typografie that you’ve initiated yourself. As a designer who’s work is embedded in materials and the practical joy of making, how do you relate to that?

KM

I think the ideal would be a mixture of the two. Originally, I’m not a real intellectual. In that sense, Wigger (Bierma, co-founder of Werkplaats Typografie) clearly represents the word. Armand (Mevis, who currently teaches at WT) also is a doer and an important engine for WT. We just finished the annual selection process, where out of 125 applicants we admitted 9 students for the next year. We’re looking at how this group is composed, and are trying to create a good balance between the workers and theoretians.

Look, design or maybe life itself is about questioning the traditions. If you’re making a bookcover, you have to relate to all bookcovers that have been made before. To students I often say, try to act as if you don’t know what a book is, like you’ve never seen a bookcover before. Ask yourself, what kind of thing is that? Does it have to be strong? Does it need a dustjacket? That is simply impossible. But I think something like that would be the ideal situation, to ask a series of questions that have not yet been answered by many others already. And often in a very solid ways too, seemingly impossible to improve.

HL

Do you feel limited by tradition then?

KM

No, to me it’s a point of reference. In that sense I’m a Darwinist. I believe in evolution, more than in in revolution. Look at the introduction of the Macintosh, bringing new technical possiblities that thoroughly changed the graphic design trade. But still, you’re relating to Piet Zwart and everything that came before and after.

HL

How do your students at the WT relate to that?

KM

Of course this is different for each individual, but it’s obvious that there’s a strong demand for information. Take a golden oldie like Sandberg… Students sense there’s something original and sincere about him and his work, something organic… Which causes us to have an earlier publication translated in English. It’s about permanently questioning history. In regard to evolution, I grew up as a modernist, and I’ve always felt as a socialist. Still do. As long as the world is not a perfect place, things will have to change. Nobody will benefit from preserving the status quo as this will only lead to decay. So, in order to achieve a better life, change is neccesary. This is why you won’t find me idealising old techniqes like letterpress or lead type. I’m not a traditionalist!

HL

Running the screenprinting lab at the Rietveld academie one day a week, causes me to stay open minded and flexible. Sometimes I think I get more out of it that the students I work with…

KM

For me teaching is very important as well. Without teaching, this book (Printed Matter) might never have been published. I very much enjoy the interaction with students. Despite my busy schedule, going back and forth to Arnhem to be at the WT gives me a shot of energy. It’s the same questions all over, but each generation has a new ways to find an original answer to them. It’s very rewarding to see that happen.

HL

You often collaborate with students, as you do designing the OASE series. In fact the original concept of the WT was based on the idea of tutors and students working side by side. At the moment Karl Nawrot (a former WT student) is busy in your studio. What are you currently working on?

KM

Karl collaborated with me executing the Architecture As Craft project (2009), but we’re currently occupied with making French balconies for a new builing by the Austrian architects Baumschlager Eberle in IJburg (new citydistrict in Amsterdam), as well as wall decorations. Our initial proposal to add type to the building was declined, so that is why we came up with a more abstract design using pixellike shapes. For the other building the design will be more organic. Eventually there will be six of those buildings.

HL

How did you start that process?

KM

The building is called Solid. The idea is that it’s going to be used in a multifunctional way. Each user can define their own space. The building should last for a hundred years, so the notion of durability is very important. That’s why we chose coral as a motif. I often like to refer to nature. In the past I’ve worked with ferns for example.

HL

I’ve never heard you refer to nature before. I’ve always assumed that many of your ideas stem from mathematics, systems…

KM

You’re mistaken there. What matters to me are nature’s perpetual movements. To be more specific, I’m interested in the smallest particles, in structures. Plants are of course also built. I’ve made things with seeds… Maybe, in my own way, I like to imitate nature…

HL

(We’re looking at a maquette) Karl’s student work, being based on his personal approach to drawing, seemed to be very different compared to most other WT students. Did the type of students that is admitted to WT change over the years?

KM

Yeah, that is part of the same evolution. I think that this school, well, at least this is my ideal, doesn’t celebrate our profession, but permanently discusses it. As Hans (Gremmen, former student WT)) put it, we’re striving for a certain seriousness. But without any dogmatism. If tomorrow somebody discovers something that was never seen before, that will be the thing that matters. Like Paul Elliman (parttime tutor at WT), who’s now introducing the element of a sound unit to the school. This connects to your previous question about doing and thinking. Stuart Bailey (now editor of Dot Dot Dot magazine) who initially was a real doer, developed into a kind of theoretical professor. People all follow their own path that don’t necessarily have to lead to great book- or poster designs. That’s why I hope and think that Armand and me can stimulate this diversity.

HL

The WT was and is closely connected to your work and personality, which I expect, attracks a certain breed of students. Aditionally, the setup there, one small building where until recently you had your own studio as well, is pretty intense. A bit like a monastry. How do you relate to that?

KM

The students mainly keep each other busy. As a group they spend more with their fellow students that with me. Look, they are all responsible for their own development. From ten years of WT students, several have made it, so to speak, but this is not my personal achievement at all. Everything is already present in themselves. I believe that education should be facilitating, that one should believe in people’s capacities. This is something I learned while being a student myself. Rather than those who needed proof of my capabilities, the unconditional trust given by specific teachers meant a lot to me. Sometimes you don’t know if and what will come out of a person, but this is what really matters.

HL

To what extend do you follow your ex-students?

KM

I like to believe in an organic course of events. I’m not actively looking for things, but if it’s there, it’s there. I never study other designer’s output because that doesn’t work for me. I’m not a member of any organisation or club either, and for similar reasons. Rather than the expected stimulation, looking at other peoples beautiful work would demotivate me. Shortly after I graduated, I was awarded a prize for the best student work, which embarrased me. My friends sollicited for jobs at design firms, but at the time I was too insecure about my own capacities. In a way I still am. In retrospect this was one of the reasons why I withdrew in the coutryside, away from Amsterdam and all the intimidating things happening there. You know, people are so easily influenced. I needed the distance so I could focus on my own development rather than trying to be part of the scene. Anyway, the most important limitations live within yourself, so it’s crucial to find out who you are and where your specific qualities lie.

HL

Three years ago you moved from Laag Keppel (a small village near Arnhem) to Amsterdam. What did you expect from the change and are there things you’ve always wanted to do that you finally have the time for now?

KM

I was looking forward to spend more time with my wife Lous and my grandchildren, do a little printing, make some plans… But being here, work has become increasingly busy. To be honest, I haven’t had the time to really think about that. But things go well!

HL

What about making your monoprints? Is there any time at all to play?

KM

Absolutely. But usually there’s a specific occasion. Like every year, I’m printing diplomas for my students. I’ve once started that, and now it’s impossible to quit. They’re counting on it!