Bison bison

Bison bison fenced in near Badlands National Park, South Dakota 2006.

Bison bison fenced in near Badlands National Park, South Dakota 2006.

Text Harmen Liemburg, published in Objects in Mirror, The Imagination of the American landscape.

Bison bison

On a visit to the United States you will inevitably come across it at some point: the American bison or buffalo pictured at the bottom of the National Park Service emblem. I have often wondered why he (sorry ladies, his crown jewels are clearly visible) stands brooding, his head turned westwards. It must be dark memories of a time when nature conservation was not yet part of the collective consciousness.

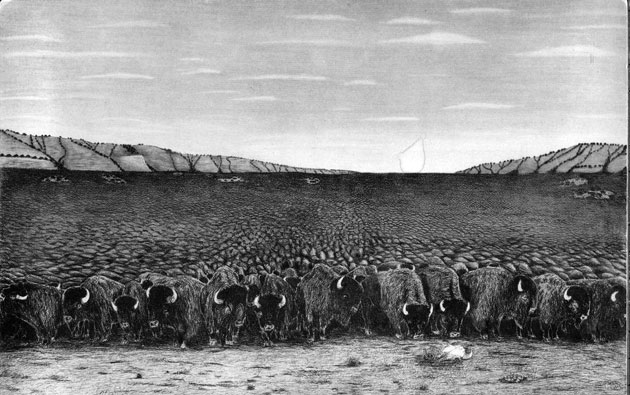

Buffalo on the March, M.S. Garretson, courtesy Kansas State Historical Society.

There was a time when Bison bison (its scientific name) thundered over the endless plains in vast herds. For the original inhabitants of the Great Plains (roughly the area between the Rocky Mountains and the Mississippi River), he was an abundant source of life. They only took what they needed for their own use, and used every part of the animals they were able to kill.

For thousands of years the herds were able to recover from these relatively small losses, but from 1500 things began to change. First, Spanish conquistadors introduced horses into the region. Around 1800, the Indians learned to pursue the bison on the fastest horses, greatly increasing their effectiveness and range as hunters. Firearms then found their way to the bison hunters, further improving accuracy. However, it was the arrival of an endless stream of white colonists in the 19th century – and their confrontations with the Indians – which heralded the end of the great bison herds. Among the first settlers were fur and other hunters who made their living by selling the meat and hides. Around 1870, hundreds of thousands of bison hides were being sent by train and wagon to the cities to the east each year. By the winter of 1872-73, that number had reached 1.5 million.

Shooting bison from the train proved to be so easy and popular with passengers, that the Kansas Pacific line considered it worthwhile employing its own taxidermist to prepare hunting trophies. (From The West)

Commercial hunters were not the only ones looking to profit from the bison. Following the construction of new railway lines that connected east and west, train operators offered tourists the opportunity to shoot at bison from the windows of their compartments, pausing only when the ammunition ran out or the barrel of the gun became too hot. There were even contests. In one of them, someone from Kansas killed 120 bison in 40 minutes. A record! The scout ‘Buffalo’ Bill Cody shot more than 4,000 bison in two years. The prairie was littered with abandoned carcasses. When the stench of rotting flesh had faded, others earned a living by collecting the skulls and bones for use in the fertiliser and pigment industries.

The End, M.S. Garretson, courtesy Kansas State Historical Society.

Some government officials promoted the destruction of bison herds as a way of beating their Indian enemies, who fiercely resisted the white colonisation of their habitat. Not long after, military commanders were given the order to allow their men to kill bison. Not to feed the troops, but purely to starve the Indian tribes and force them to surrender. Around 1880 this systematic slaughter was almost over. Where once millions of bison roamed, there were now just a few thousand left. Their numbers would decline even further, until the largest wild herd – a few hundred animals – found protection in the isolated valleys of the first area protected from commercial exploitation, Yellowstone National Park.

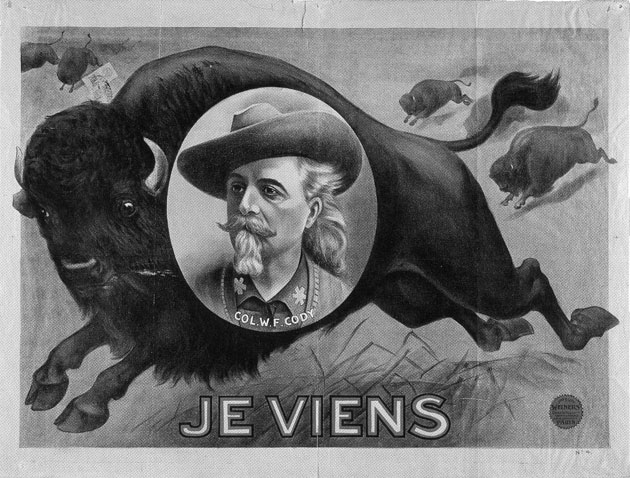

Je viens (I am coming), poster announcing performances in France, early 20th century. Buffalo Bill’s fame was so great that the name of his Wild West show did not even have to be mentioned to draw crowds. Chromolithography, Weiners, Paris. (From Buffalo Bill’s Wild West)

By the time his work in the West as a celebrity guide for hunting parties of royals, notables and wealthy urbanites came to an end, William ‘Buffalo Bill’ F Cody was already a national legend. He started a travelling show in which his exploits were re-enacted for a wildly enthusiastic audience, complete with attacks by hostile Indians, heroic cowboys and lots of shooting. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West & Congress of Rough Riders of the World was a hit for years, and would make an important contribution, in America as well as Europe, to the mythology of the Wild West.

Cute Park ranger at Kings Canyon NP with National Park Service embroided emblem.

The first national parks, in the early days still protected by the cavalry, grew to become a National Park System. In 2011, the National Park Service managed a total of 397 units. In addition to large and medium national parks, the NPS administers National Seashores, Monuments, Historical Sites and other types of protected areas. The current emblem was introduced in 1953. The bison and sequoia represent the wildlife and vegetation, the mountains and water represent the scenic and recreational functions. The arrowhead, which frames the emblem, represents historical and archaeological values.

The bison actually does double duty. It is also the most important symbol in the seal of the US Department of the Interior, under which the NPS falls. Since its introduction, the NPS emblem has been implemented in a range of versions and materials. The popular version with the dark brown background is used on park rangers’ uniforms. Attempts to replace the emblem in 1966 with an abstract logo designed by Chermayeff & Geismar Ass. had to be abandoned following strong staff opposition. Like the characteristic ‘Smokey the Bear’ Stetson hat, the emblem (along with the embossed leather hat band and belt with sequoia cone) is beloved by those who have the privilege of wearing the regalia.

CrowdSpring U.S. Department of the Interior winning logo proposals.

After 60 years, people at the Department of the Interior apparently tired of the old-fashioned round seal, but following the budget cuts made by the Bush administration there does not appear to be enough money available to contract a reputable design agency. What the hell, everybody is a designer these days, right? In summer 2011, the ministry organised a design competition via CrowdSpring, ‘the world’s #1 marketplace for logos and graphic design’. A form of ‘crowd designing’, in other words. For a fistful of dollars, a leaner and meaner Department of the Interior received no less than 617 proposals, four of which have been selected for further development…

Buffalo burger by up-and-coming chef Marcus Samuelsson, courtesy The Express-Times, 31 May 2010.

And Bison bison itself? Besides the semi-wild herds in a handful of national parks, it is primarily reared for its skin and meat. Buffalo burgers are more expensive than the average burger, but you get more for your money. The meat contains less cholesterol, fat and calories than beef or chicken burgers. It has a coarser structure and tastes sweet and tender. Have you tried a buffalo burger yet?

Sources

David A. Dary, The Buffalo Book, The Full Saga of the American Animal, Swallow Press / Ohio University Press, 1989 revised edition.

Geoffrey C. Ward, The West, An Illustrated History, Little, Brown & Co, Toronto, 1996.

R. L. Wilson, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, Random House, New York 1998.

Dayton Duncan & Ken Burns, The National Parks, America’s Best Idea, Knopf 2010.

American Buffalo: Spirit of a Nation, PBS nature documentary (introduction), 2008.

History of the NPS emblem and uniform: nps.gov.

– – –

Edited by: Hans Gremmen

Contributions by: Rixt Bosma, André Waardenburg, Caroline von Courten, Hans Gremmen, Venturi Scott Brown and associates, Harmen Liemburg, Raymond Frenken and Helmut Smits

Design: Hans Gremmen

Publisher: Fw:Books with FOTODOK

distribution NL: Ideabooks

Language: English

Size: 140 x 190 mm 128 pages / colour / paperback

ISBN 978-94-90119-15-7

See also Home Field

See also Urban Forest Project